When someone goes to a hospital, before admission they typically get handed a lengthy package of forms with minimal explanation. At the same time, that someone is usually feeling ill and simply wants medical help. Sometimes this means that they just sign the forms as directed, without a thorough understanding of what exactly they are consenting to. Today we look at some common issues that come up with these forms so we can better understand what we are signing, should we or our loved ones need hospital care.

“Consent” v. “Informed consent”

Preliminarily, we note that there is a difference between consent and informed consent. The former means our basic right to accept or decline a medical intervention or procedure, while the latter is a method to give guidance to hospitals and doctors about their duty to inform, making sure that patients have certain key information. These ideas overlap somewhat, in that any consent requires some idea of what one is consenting to, and informed consent is a typical mechanism to prove that someone had adequate information in order to actually consent to a treatment. “Informed consent” is often the term used legally to describe what happens at a hospital, so despite the differences between the two concepts this article will use them somewhat interchangeably.

Hospital consent form basics

Most hospitals combine various documents in a packet presented to prospective patients in order to be admitted. These include general, non-specific consent to medical care that is considered routine, financial consent and financial responsibility documents, HIPAA acknowledgments, consent for photography and other media, and patient rights information. Often, they also include agreement to arbitration, meaning the patient agrees that they are giving up their right to sue and that a professional arbitrator, versus a jury or court, will hear claims for malpractice or other wrongdoing. There is no single national standard for these forms, and hospitals draft them based on a combination of state-specific and federal laws and rules. After admission, if an invasive procedure is considered there may be a need for another form and signature. While there is no general rule that medical consent must be in writing, some state laws require more specific information and additional forms and signature such as forms for surgery, anesthesia, sterilization, HIV testing, mental-health treatment, and other sensitive matters. These generally include risks, benefits, alternatives (including doing nothing), and whether a doctor-patient discussion occurred.

Principles and authorities underlying consent forms

The AMA describes informed consent as “fundamental in both ethics and law” and requires physicians to disclose diagnosis, risks, benefits, and alternatives as described in their Code of Medical Ethics, Opinion 2.1.1. And case law discusses informed consent as necessary for protection against medical battery/unauthorized treatment, as well as the negligent failure to convey a material risk. Federal regulations also underly some aspects of hospital consent forms, as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have rules about consent forms for hospitals that receive funding from them.

Common problems with current consent forms

Some hospital consent forms are written at a college level, while not all patients read at this proficiency. Many folks complain that these forms are too long, reducing the likelihood that everyone will fully and carefully read them. And obviously people seeking hospital admission are sick, making capacity to understand and time pressure issues that can impact the comprehension of all the details in these admission forms. These patients who may be in pain or sedated are susceptible to thinking they have no choice and may be told to “just sign” a form, without a real-life conveyance of key information. As noted above, admission forms often bundle unrelated documents, covering a wide variety of topics, creating potential contracts of adhesion.

Case study 1: UT Southwestern Medical Center

The hospital admission form for the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center gives us an example of what these documents look like around the USA. Among other things, this form includes the following clauses:

“I voluntarily consent to the procedures and services that may be performed for me on an inpatient or outpatient basis under the general and special instructions of my physician, and/or his/her assistant or designee. I understand that these procedures and services may include but are not limited to emergency treatment or services, laboratory procedures, imaging services, medical or surgical treatment or procedures, anesthesia or hospital services.”

“I acknowledge that any supplies, medical devices or other goods sold or given to me are provided “as is”, and that UT Southwestern disclaims any express or implied warranties related thereto.” (Emphases added.)

Some problems with this form include that it seeks consent to “procedures,” up to and including surgery, before a patient has even seen a doctor. And its claim that any medical devices used are offered “as is,” seeming to circumvent normal products liability laws, would be more appropriate at a used clothing shop, versus an entity trusted with our health.

Case study 2: Los Angeles County Department of Public Health

Public hospitals in LA, California use an admission form with this language:

“I agree that the Hospital/Clinic may use and get rid of any tissue, organ, matter or other item removed from my/patient’s body.” (Emphasis added.)

This clause, dealing with how our body parts or tissues are to be handled, raises red flags given the “market” in these items. While the sale of body parts is illegal, hospitals can charge handsomely for “services” relating to organ or tissue donation for research or other purposes. So, signing this form would allow the hospital to profit from our tissues without clearly informing us of this fact or sharing proceeds from such tissues or organs. And whether due to privacy concerns about our DNA, a general respect for our bodies, or other issues, many people would prefer that these materials be destroyed. And economic factors might also come into play: do we want hospitals to have an incentive to potentially remove more body tissue than medically necessary?

Imbalance of power in contracts of adhesion

Contracts of adhesion are often considered against public policy and therefore not enforceable in court. According to the Cornell University’s Legal Information Institute, “[a]n adhesion contract exists if the parties are of such disproportionate bargaining power that the party of weaker bargaining strength could not have negotiated for variations in the terms of the adhesion contract. Adhesion contracts are generally in the form of a standardized contract form that is entirely prepared and offered by the party of superior bargaining strength to consumers of goods and services.” Back in 1976, the California case of Wheeler v. St. Joseph Hospital declared that an admission form was in fact a contract of adhesion based on a lack of meaningful explanation of what an arbitration clause meant. This case law was later negated by California statute, Code of Civil Procedure § 1295. This section explicitly states that a properly drafted medical service arbitration contract “is not a contract of adhesion, nor unconscionable nor otherwise improper[.]”

Closing thoughts for Patients

Hospital admission forms are essentially contracts between the patient and the providers. Under normal contract law, prospective patients can cross out specific items, add limiting conditions (e.g. no disclosure to Health Information Exchanges), or write out a separate letter or statement of limitations to attach to these documents. At the same time, absent an emergency, a hospital may refuse admission for a person who wants to negotiate about their standard forms. And since these forms are often presented electronically (such as on a tablet), it is likely a good idea to ask for a printed version to both allow better comprehension and enable folks to directly modify them easily. The time to learn about these forms is before we need to go to the hospital. With greater education of the public, and perhaps legislative reform, we can avoid many of the problems discussed above.

RECENT NEWS

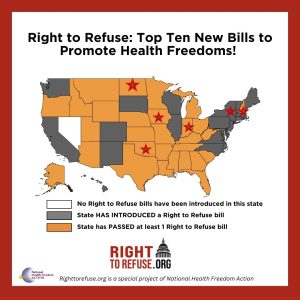

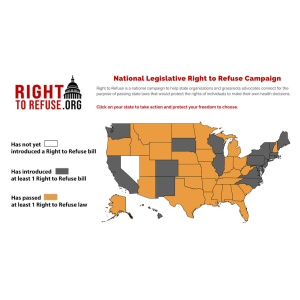

Right to Refuse: Top Ten New Bills to Promote Health Freedoms!

January 22, 2026

Will Health Freedom See Gains In 2026?

January 8, 2026