In a major April 18 opinion, Judge Kathryn Kimball Mizelle of the US District Court, Middle District of Florida, granted a summary judgement and ruled that the CDC’s February 3, 2021, mask rule for travelers, commonly known as the Mask Mandate, is unlawful. The rule requires masks, “in airports, train stations, and other transportation hubs as well as on airplanes, buses, trains, and most other public conveyances in the United States.” The rule includes criminal penalties for non-compliance.

In sum, Judge Mizelle found that the Mandate goes beyond CDC’s statutory authority and also that it violated the rule-making process in the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), improperly invoking the good cause exception to the public notice and comment requirements of rulemaking, and failed to adequately explain its decisions. The case was brought by Health Freedom Defense Fund, Inc. along with two individual plaintiffs.

Impracticable to Get Public Comment?

On January 21, 2021, a day after taking office, President Biden issued an executive order titled, “Promoting COVID-19 Safety in Domestic and International Travel.” The order said that mask wearing, “can mitigate the risk of travelers spreading COVID-19.” About two weeks later, on February 3, the CDC published its Mask Mandate. This was done without following the APA’s 30-day public notice and comment process. Defending this lapse, CDC found that, “it would be impracticable and contrary to the public’s health” to put off the Mandate to allow public comment. Plaintiff’s asserted that there was no good cause exception to skip the notice and comment process under the APA rules and the court agreed. Merely stating that there was a public health emergency without offering any further specific reasons did not constitute a good cause exception.

The CDC also argued that the Mandate was published as a CDC “Order” and not a “Rule” thus it would be outside of the requirements and scope of the APA. But the CDC abandoned that untenable position because the Mask Mandate is a generally applicable standard “governing conduct and rights.”

Judge Mizelle notes that the APA mandates that courts, “hold unlawful and set aside agency action” which is arbitrary or capricious or beyond statutory jurisdiction or when a rule is issued, “without observance of procedure required by law.”

Anxiety and Constricted Breathing

The plaintiffs, Health Freedom Defense Fund, Ana Daza, and Sarah Pope, sued to challenge this mandate on July 12, 2021. The two individual plaintiffs travel by airplane routinely. Ms. Daza suffers from anxiety which is worsened by wearing a mask. She alleges that, “the government does not recognize [her] anxiety as a basis for a[ medical] exemption” from CDC’s mandate. Ms. Pope flew often prior to the pandemic, but now she flies less since the “constricted breathing from wearing a mask” exacerbates her panic attack disorder. These circumstances established the requirements for standing to bring a case forward, including “alleged harms sufficient to establish standing in one’s own right” and imposing “a legal obligation on the individual Plaintiffs to wear masks when using public transportation.”

“Creatures of Statute”

Two important grounds for plaintiffs’ suing are that the Mandate goes beyond CDC’s statutory authority delegated by the legislature and also that even if it did not, the delegation statute improperly delegated law-making power from the Congress to the CDC. As “creatures of statute,” administrative agencies, “possess only the authority that Congress has provided.” CDC is authorized to make rules necessary to prevent the transmission of communicable diseases from foreign nations or between US states. In making its policy, CDC relied on a portion of the Public Health Services Act (PHSA) of 1944 allowing regulations that aim at, “identifying, isolating, and destroying” diseases. Since 1944, the PHSA has, “generally been limited to quarantining infected individuals and prohibiting the import or sale of animals known to transmit disease.” It has been “rarely invoked” until recently. Within the last two years, CDC has tried to wield, “the power to shut down the cruise ship industry, stop landlords from evicting tenants who have not paid their rent, and require that persons using public conveyances wear masks.” The first two of these have been found to exceed CDC’s authority by prior court rulings.

“Sanitation,” Circa 1944

By statute, CDC has the power to issue regulations which, “in [its] judgment are necessary” to stop the spreading of communicable diseases. The next sentence in the regulations relied upon, “informs the grant of authority by illustrating the kinds of measures that could be necessary: inspection, fumigation, disinfection, sanitation, pest extermination, and destruction of contaminated animals and articles.”

CDC argues that the Mask Mandate is a “sanitation” measure or “other measure” comparable to sanitation. Judge Mizelle noted that the meaning of “sanitation” must be reviewed in the context of the word’s meaning in 1944, and she therefore relied on contemporaneous dictionary entries: it can mean, “measures that clean something or that remove filth, such as trash collection, washing with soap, incineration, or plumbing.” And it also refers to, “measures that keep something clean.” The context of the relevant law shows that both “sanitation” and “other measures” refer to actions that clean something and not those that, “keep something clean.” In a key quote, Mizelle posits that, “Wearing a mask cleans nothing.” It neither sanitizes the person wearing one nor the transit vehicle.

CDC’s Authority Over Individuals Limited

Another key flaw in the “masking-as-sanitation” argument is that the authorizing laws do not give CDC power to act directly on individuals. The Mandate directly regulates persons, while the purported authorizing laws only contemplates the regulation of property interests. All of the key words in the relevant law, “inspection, fumigation, disinfection, sanitation, pest extermination, and destruction” are not normally used to refer to something done to a person. They are instead tied to, “specific, tangible things on which the agency may act.” Also, the court found that the Mandate is akin to “quarantine” in limiting folks’ liberty. And it, “enlists local governments, airport employees, flight attendants, and even ride-sharing drivers to enforce these removal measures.”

Vast Economic and Political Significance

Another issue is the Major Questions doctrine. This holds that Congress must “speak clearly” if it is to assign decisions with vast economic and political consequences to an administrative agency. The Mandate is an “economically significant regulatory action,” meaning that it is likely to have an annual effect of $100 million or more on our economy, to cause a major increase in consumer prices, or to have significant adverse effects on the economy. And there is no evidence that Congress intended for the CDC to, “invade the traditionally State-operated arena of population-wide, preventative public-health regulations.” Judge Mizelle concluded that limiting relief to only the folks suing would be impractical, and therefore ordered a nationwide halt to the Mandate.

RECENT NEWS

One hundred Days of Making America Healthy Again

May 15, 2025

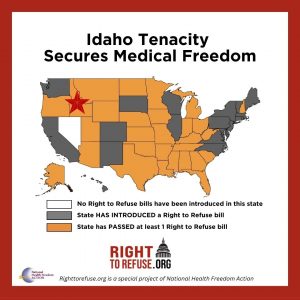

Idaho Tenacity Secures Medical Freedom

May 12, 2025